Capturing the Power of a Picture Book

Written by guest author: Samantha Cleaver

Interactive Read Aloud and Modern Literacy in the Library

Many of us have fond memories of library class. The musty smell of the books on shelves. The satisfying thunk of the Dewey Decimal card drawers. The thrill of checking out our own books…The school library has come a long way since then. Today’s school library is where students learn modern view of literacy skills that they will carry into adulthood. Indeed, the skills that children learn in the library will shape their daily experience as adults. To be effective, library teachers need a way to maximize their most powerful tool—picture books—to prepare students to navigate a world that is constantly changing and where the abilities to think critically, evaluate media, and empathize are more important than ever. That’s where the LIRA (library interactive read aloud) comes in.

Why Picture Books?

Picture books are powerful. They serve as vibrant mirrors, reflecting students’ own experiences and fostering spaces where empathy for others can flourish. These literary gems offer diverse entry points for all types of learners—some are drawn in by the captivating illustrations, while others find their gateway through the written text, and yet more immerse themselves in the rhythmic cadence and eloquent flow of an adult reading aloud. The power of picture books lies in their ability to weave a tapestry of connection, resonating with readers in unique and multifaceted ways.

Picture books are also an ideal space to teach modern literacies because they are:

Accessible: Picture books invite readers into stories through illustration and text. This combination of picture and print make picture books accessible for students at a range of English proficiencies. In particular, picture books bring complex nonfiction topics to life and help build background knowledge and vocabulary about real-world topics (Bingham et al., 2018).

Complex by Design: Since picture books are read aloud, authors can use language and vocabulary that younger students aren’t ready to read on their own but are ready to engage with. In addition, the illustrations in picture books add meaning to text and allow for deeper analysis. This complexity allows teachers to engage young students in modern literacy, including systems and critical literacies.

Invitations to Empathy: Empathy involves the ability to understand that others have different experiences, and the ability to understand what others think and feel (Kucirkova, 2019). It’s a skill that children need to have as they become critical thinkers and global citizens. Children as young as three or four can engage in empathy and perspective-taking (Wellman, 1992), and picture books help build empathy by showing how characters respond to situations and inviting readers to feel alongside them.

Foster a Love of Literature: At the heart of what library teachers do is foster and spread a love of literature and reading. Having experiences with picture books from a young age, and continuing throughout school, is one way to ensure that all students identify as readers.

The Importance of Socially Relevant Books

Since the origin of the Reader Response theory (Rosenblatt, 1978) the idea that readers interact with text has evolved. Now, we talk about children using books as “windows, mirrors, and sliding-glass doors” (Bishop, 1990), meaning that books provide a way for children to have their own experiences confirmed (mirrors), understand others’ experiences (windows), and as a transformative experience (sliding glass doors).

These ideas are most prominent in the discussion about socially relevant, diverse, multicultural literature. The growth of diversity present in children’s literature is well established (Adukia et al., 2023; Lee & Low, 2018). This is important because books show children what is possible, and impact their academic achievement:

- The way children are represented in books can contribute to their understanding of what they can do, and where they fit in society (Adukia et al., 2023).

- The way that different identities are included or not included in books shapes how children view their and others’ potential (Adukia et al., 2023).

- When children received instruction using culturally relevant texts their comprehension growth outpaced that of peers who did not receive the same instruction (Clark, 2017).

Having access to and experiences with socially relevant books makes a difference for all kids, particularly those who have been underrepresented in children’s literature.

From 1994 to 2017, 37% of the U.S. population are people of color; 13% of children’s books contain multicultural content. And, in 2017, Black, Latino, and Native authors wrote 7% of new children’s books (Lee & Low, 2018).

In 2023, University of Chicago researchers used A. I. technology to analyze images in children’s interactive read aloud books for kindergarten and found that characters in children’s books are overwhelmingly white and male. They found that even in recent years, children’s books have grown less representative in terms of skin color (Adukia et al., 2023).

The Research on the Interactive Read Aloud

The Big Five

As children learn to read, they must learn and use “the Big Five”: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension (based in oral language). Interactive read aloud books for kindergarten is one of those reading activities that incorporates models, teaches, and reinforces four of the five, including phonemic awareness (Swanson et al., 2011; Ukrainetz et al., 2000); fluency (Aykol, 2012; Ceyhan & Yildiz, 2021; Hurst et al., 2011; Lane & Wright, 2007; Myers, 2015; Muller, 2005; Spencer, 2011); vocabulary (Beck & McKeown, 2007; Brabham & Lynch-Brown, 2002; Cleaver, 2018; Maynard et al., 2010); and comprehension (Ceyhan & Yildiz, 2021; Giorgis & Johnson, 2003).

Love of Reading

Engaging in IRA increases students’ motivation to read (Arial & Albright, 2006; Ceyhan & Yildiz, 2021; Duncan, 2010; Fox, 2008; Ivy, 2003; Trelease, 2013) and peaks students’ curiosity in reading (Spencer 2011). Students’ motivation increases when texts are relevant to them (Kindle, 2009), and when reading is a social experience (Ceyhan & Yildiz, 2021; Tompkins, 2006).

Modern Literacy Skills

During IRA lessons, students are active listeners and, because they are not doing the work of decoding, students can think and engage with content and ideas. As teachers read, model, and engage students in conversation and inquiry, students can move from literal to critical thinking.

Make the Shift from Learning to Read to Reading to Learn

As teachers model their thinking about a book, and how they are using it in different ways, students get an important view into the teacher’s mind (Tompkins, 2006). This is particularly important for older elementary students who are shifting from learning to read to reading to learn (Boyd & Devennie, 2009).

Challenges to the Modern School Library

Today’s librarian does more than teach students how to check out books. Modern librarians teach, plan with classroom teachers, provide professional development, facilitate technology use and support, and serve on school committees (Lance & Kachel, 2018). Librarians are leaders and resources for teachers and the school community (Lance & Schwarz, 2012).

The Impact of School Librarians

Since 1992, studies have shown consistent, positive correlations between high-quality libraries and student achievement (Gretes, 2013; Scholastic, 2016). When schools have full-time qualified librarians, students score higher on standards-based language arts, reading and writing tests regardless of school characteristics, including income (Lance & Hofschire, 2011).

Perhaps most important, strong school library programs benefit students who are most vulnerable and at-risk; students of color, those who attend low-income schools, and students with disabilities (Coker, 2015; Lance & Kachel, 2018).

School Library Trends

Public education was greatly impacted by the COVID 19 shutdowns and shifts. One of the changes that the pandemic brought was a significant reduction in the number of school librarians, particularly for students in low-income and low-resourced schools (Lance & Kachel, 2022).

This loss cannot be explained solely by funding shortages. Other positions (e.g., instructional coaches and administrators) have been growing at impressive rates Lance & Kachel, 2021). At this point, at least a year out of the pandemic, there are fewer school librarians than ever and inequitable access to school librarians (Lance & Kachell, 2022). What is unknown is whether the current losses are temporary, or if this is yet another “new normal” post-COVID.

What Librarians Bring

The fact remains that there are not enough high-quality library programs to meet the need. Where there are school librarians, the role is changing. Increasingly, schools are turning to librarians to be experts in modern literacy skills, including critical thinking, media literacy, and systems literacy. For example, the vast majority of teachers (94%) regard critical literacy as important in a Reboot Foundation survey, however, 44% of teachers reported that there were no media literacy courses in school.

Where school librarians’ roles have been cut and replaced, the modern view of literacy skills remain an important need and IRA lessons that engage students with relevant literature, discourse and inquiry, like those using the LIRA framework, can fill that gap.

LIRA and the Science of Reading

The Science of Reading, or reading instruction that incorporates phonemic awareness, phonics, word reading, fluency, vocabulary, language, comprehension, and domain knowledge, is the current focus in reading instruction (Shanahan, 2021). The Science of Reading can get distilled down to just phonics and word reading, but that’s not the case. Research on reading overwhelmingly supports IRA as a way to build students’ language and comprehension (Swanson et al., 2011). Furthermore, the Science of Reading movement encourages students to be taught reading not just in their primary classroom, but across disciplines (Schwartz, 2022). That’s where the library comes in.

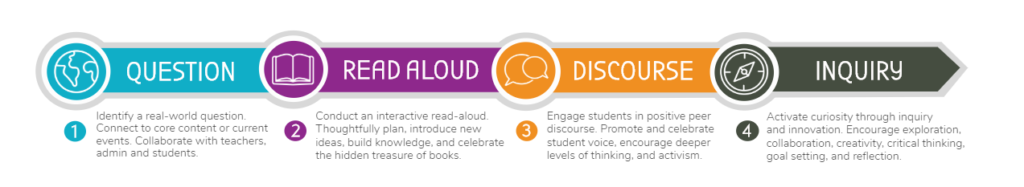

As we learn more about how to best teach children to read, library instruction and LIRA can support and enhance classroom reading goals. Classroom IRA is focused on building those Big 5 reading skills (phonemic awareness, fluency, vocabulary, comprehension). Library IRA is focused, first, on challenging students to do more with what they read in books through questioning, discourse, and inquiry, and second, on building students’ comprehension and vocabulary.

Library interactive read aloud (LIRA) supports and extends the work that teachers do in the classroom. It also provides an opportunity for students to use books in new ways to strengthen modern literacy skills. The LIRA Framework links core instruction to culturally and socially relevant literature through interactive read aloud books. In the LIRA Framework, IRA is the conduit and jumping off point to explore and engage with new ideas and deep topics.

Conclusion

School libraries are where students learn modern literacy skills that they will use in their daily lives. Librarians’ most powerful tools—picture books—are already on the shelves. When paired with LIRA lessons, socially and culturally relevant picture books create opportunity and space for students to learn and practice modern literacies including critical literacy, systems literacy, social literacy, agentic literacy, and media literacy.

Library Interactive Read Aloud is an accessible way for school librarians, or teachers in schools that do not have the resource of a school library, to harness the learning that is inherent in picture books and empower students to develop the skills needed to engage with an ever-changing world.

About the Author

Samantha Cleaver, PhD, is a teacher and instructional leader. She is an expert on interactive read aloud and Active Reading, a way to read with children rather than to them. She is the author of two books about Active Reading, Read with Me (Rowman & Littlefield, 2018, written with Munro Richardson) and Raising an Active Reader (Rowman & Littlefield, 2020).

References

Adukia, A., Eble, A., Harrison, E.,Hakizumwami, B. R., & Szasz,T. (2023). What we teach about race and gender: Representation in images and text of children’s books. Becker Friedman Institute Working Paper. Retrieved from: https://bfi.uchicago.edu/working-paper/2021-44/

Beck, I. L., & McKeown, M. G. (2007). Increasing young low-income children’s oral vocabulary repertoires through rich and focused instruction. The Elementary School Journal, 107, 251-271.

Bingham, G. E., Venuto, N., Carey, M. & Moore, C. (2018). Making it REAL: Using informational picture books in preschool classrooms. Early Childhood Education Journal, 46, 467-475. Retrieved from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10643-017-0881-7

Bishop, R. S. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding-glass doors. Perspectives: Choosing and using books for the classroom, 6(3). The Ohio State University.

Brabham, E. G., & Lynch-Brown, C. (2002). Effects of teachers’ reading-aloud styles on vocabulary acquisition and comprehension of students in the early elementary grades. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94, 465-473.

Ceyhan, S., & Yildiz, M. (2021). The effect of interactive read aloud on student comprehension, reading motivation, and reading fluency. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 13(4), 421-431. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1298033.pdf

Clark, K. F. (2017). Investigating the effects of culturally relevant texts on African American struggling readers’ progress. Teachers College Record, 119(6). Retrieved from: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1123432

Cleaver, S. (2018). Effects of short-term structured teacher training in Active Reading on language and reading outcomes of students at risk and not at risk for reading failure, teacher implementation of Active Reading, and teacher perceptions of read aloud practices. [Doctoral dissertation] University of North Carolina at Charlotte. Retrieved from: https://www.proquest.com/openview/028158ae3861eb809d967a9b66663132/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750

Coker, E. (2015). The Washington State library study: Certified teacher-librarians, library quality and student achievement in Washington state public schools. Seattle, WA: Washington Library Media Association.

Duncan, S. (2010). Instilling a lifelong love of reading. Kappa Delta Pi, 46(2), 90–93.

Giorgis, C. & Johnson, N. (2003). Children’s books: celebrating literature. The Reading Teacher, 56(8), 838–845.

Gretes, F. (2013, August 12). School library impact studies: A review of findings and guide to sources. Prepared for the Harry & Jeanette Weinberg Foundation.

Hurst, B.,Scales, K., Frecks, E. & Lewis, K. (2011). Sign up for reading: students read aloud to the class. The Reading Teacher, 64(6), 439–443.

Johnston, V. (2016). Successful Read-Alouds in Today’s Classroom. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 52(1), 39–42. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/00228958.2016.1123051

Kindle, K. (2009). Vocabulary development during read-alouds: primary practices. The Reading Teacher, 63(3), 202–211.

Kucirkova, N. (2019). How could children’s storybooks promote empathy? A conceptual framework based on developmental psychology and literary theory. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(121). Body

Layne, S. (2015). In Defense of Read Aloud: Sustaining Best Practice. Stenhouse Publishers.

Lance, K.C. & Hofschire, L. (2011). Something to shout about: New research shows that more librarians means higher reading scores. School Library Journal, 57 (9), 28-33.

Lance, K. C., & Kachel, D. E. (2018). Why school librarians matter: What years of research tell us. Kappan, Body

Lance, K. C. & Kachel, D. E. (2021, July). Perspectives on school librarian employment, 2009-10 to 2018-19. The School Librarian Investigation—Decline or Evolution? Body

Lance, K. C., & Kachel, D. E. (2022). The COVID-19 pandemic and inequities in access to school librarians. SLIDE Institute of Museums and Library Science. Retrieved from: Body

Lance, K.C. & Schwarz, B. (2012, October). How Pennsylvania school libraries pay off: Investments in student achievement and academic standards. PA School Library Project.

Lane, H. B. & Wright, T. L. (2007). Maximizing the effectiveness of reading aloud. The Reading Teacher, 60(7), 668–675.

Lee and Low Books. (5/10/2018). The diversity gap in children’s book publishing 2018. Retrieved from: Body

Maynrd, K. L, Pullen, P. C., & Coyne, M. D. (2010). Teaching vocabulary to first-grade students through repeated shared storybook reading: A comparison of rich and basic instruction to incidental exposure. Literacy Research and Instruction, 49, 209-242.

Muller, P. (2005). Teen read week meets read-aloud to a child week in Virginia. Young Adult Library Services, Fall 2005, 23–24.

Myers, J. M. (2015). Interactive read-alouds: A qualitative study of kindergarten students’ analytic dialogue. [Doctoral thesis]. Indiana University.

Reboot Foundation. (2018). Critical Thinking Survey Report. Retrieved from: Body

Rosenblatt, L. M. (1978). The reader, the text, the poem: The transactional theory of the literary work. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Routman, R. (1991). Invitations changing as teachers and learners k-12. NH: Heinemann Educational Books, Inc.

Stripling, B. (2020). Advocating for the “Why” of School Libraries: Empowering Students through Inquiry. Knowledge Quest March/April 2020: (19-22).

Scholastic. (2016). School libraries work! A compendium of research supporting the effectiveness of school libraries. www.scholastic.com/slw2016

Schwartz, S. (2022). Why putting the ‘Science of Reading’ into practice is so challenging. Education Week. Retrieved from: Body

Shanahan, T. (2021). What is the science of reading? Reading Rockets. Retrieved from: Body

Spencer, R. R. (2011). Reading aloud and student achievement. [Doctoral thesis]. Lindenwood University.

Swanson, E., Vaughn, S., Wanzek, J., Petscher, Y., Heckert, J., Cavanaugh, C., Kraft, G., & Tackett, K. (2011). A synthesis of read-aloud interventions on early reading outcomes among preschool through third graders at risk for reading difficulties. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 44, 258-275.

Teacher Librarian Magazine (June, 2021). Data Speaks: Preliminary Data on the Status of School Librarians in the U.S. Retrieved from: https://libslide.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/SLIDE-Poster.06.2021.pdf

Tompkins, G.E. (2006). Literacy for the 21st century: a balanced approach. Prentice Hall.

Trelease, J. (2013). The read-aloud handbook. Penguin.

Ukrainetz, T. A., Cooney, M. H., Dyer, S. K., Kysar, A. J., & Harris, T. J. (2000). An investigation into teaching phonemic awareness through shared reading and writing. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 15, 331-355.

Wellman H. M. (1992). The Child’s Theory of Mind. Boston, MA: The MIT Press.